Everyone who has ever tried to introduce new technology into the practice of medicine knows how difficult this process is. The reasons are numerous, but the overarching issues are that patient safety is supremely important, and any new clinical tool must be vigorously tested to ensure its safety. Another issue is that the introduction of new tools into existing workflows has proven to be a complicated task that few wish to risk. These workflows have been developed over decades to be compliant with regulatory requirements, protect patient safety, and ensure care team collaboration and access. Introduction of new technology means disruption to these well-established workflows, potentially making the entire team’s life more difficult rather than easier.

It is interesting to note that technology helps automation in industries such as travel, hospitality, mobility, and more, but is less efficient in healthcare. One of the reasons is the fragmented nature of healthcare data, making automation of clinical, administrative or operational activities more difficult. While Amazon and Netflix can improve the consumer experience for shopping and streaming by having only a small slice of personal data in those areas, this is not possible in healthcare.

If a segment of the medical history is missing, decision-making support is not possible. Submitting a medical payment claim is unworkable if part of the patient’s work-up is not included in the documentation; insurance companies are always on the lookout for any reason to deny or reduce payment. Allowing AI to process and submit payment claims autonomously will simply not function if the radiology reporting system is not connected to the HER.

While progress has been made in interoperability, there are simply too many hubs to connect, even within a city, let alone in a state or a nation. Submitting a claim with prior authorization for a medication may not require full interoperability, but identifying health issues and gaps in care proactively, and addressing them effectively, requires near complete medical records. If a procedure was performed at one medical center, but the patient’s records at a different center do not show the results, it is a clear indication that neither center is fully aware of the patient’s health status, indicating a serious danger to the patient.

There is a perceived lack of clear evidence of clinical benefits or financial return on investment (ROI.) New technology requires the expenditure of money, time and effort. It must demonstrate some possible benefits, such as improving patient outcomes, enhancing clinical productivity, upgrading operational and administrative efficiency, increasing revenues, and/or lowering costs.

To show improved patient outcomes, you need to do real-world, prospective and controlled trials to document the promised benefits. Without that, you’re just making unsubstantiated claims, and the medical community is a tough crowd to do that to. They’ve shown to be quite uncooperative with anything that does not prove its claims through well-designed studies. A good example of this is all the various radiology AI solutions that read scans and “help” the radiologist with their workflows. All of them have FDA approval, a low bar that can be met by showing that your tool is as accurate as a radiologist in finding a defined abnormality. However, in most cases the studies show that using the AI in addition to the radiologist improves patient outcomes haven’t been done. What does that mean for those companies? Insurance companies are not paying for them and if patients want AI to assist the radiologist in reading their scans, they need to pay out of pocket. Most are opting not to, and these tools have seen limited adoption.

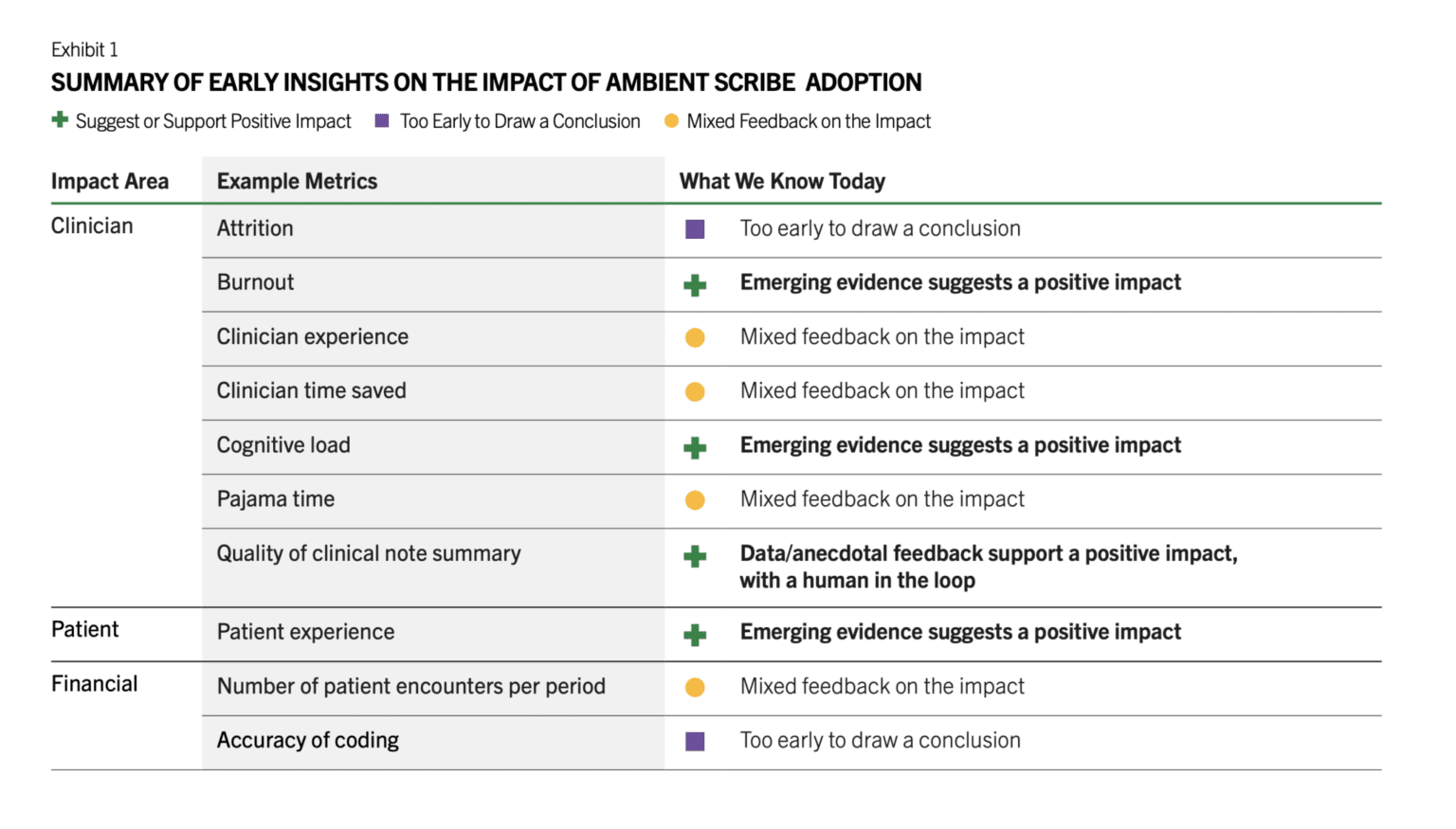

There are a number of other barriers such as the medical legal concerns by the providers, lack of the training of the staff in using them, lack of IT resources that can implement and monitor these tools, unclear regulatory framework, cost, and more. However, in the last 18 months, we have seen brisk adoption of some use cases such as ambient documentation, co-pilot function within the EHRs, and to a lesser extent autonomous coding. All of these are clinical workflow and administrative use cases. There is a reason for this. These are lower risk use cases that don’t involve clinical decisions, and none is fully autonomous. Doctors review the notes generated by ambient AI documentation tools and review any codes that are automatically created, and chart summaries are intended to save them time from reading a thick patient record but often that information is validated by the patient. It has been reported that the chart summaries contain numerous errors, necessitating physicians to review and verify the information, which reduces efficiency. There’s also emerging early evidence that there’s ROI for these tools. Peterson’s Health Technology Institute published a study that estimated lower burnout and cognitive load for physicians from the use of ambient AI documentation but the financial ROI to the health systems is not clear yet (Figure 1).

As for clinical AI tools, it doesn’t look like the studies needed are being done by companies and therefore adoption remains low. These studies take time and money, and most companies think they can magically drive adoption of their products without documenting clinical benefits. An RSNA study found that 81% of AI models dropped in performance when tested on external datasets. For nearly half, it was a noticeable drop, and for a quarter, it was significant. After these tools are approved, there’s no standard way to keep an eye on how they work across different scanners, hospitals or patient groups. In a recent interview with Health IT News, Pelu Tran, CEO and cofounder of Ferrum Health, opined that companies are not doing real-world studies to show that their tools perform as expected in that messy environment and that they result in improved patient outcomes. He calls for the buyers to demand solid evidence of clinical outcome improvement or financial ROI.

About the author

Dr. Ronald Razmi is the author of the “AI Doctor: The Rise of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare” (Wiley, 2024) and former Cardiologist, McKinsey consultant, and CEO of digital health company, Acupera. He completed his medical training at the Mayo Clinic and holds an MBA from Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management

Dr. Ronald Razmi is the author of the “AI Doctor: The Rise of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare” (Wiley, 2024) and former Cardiologist, McKinsey consultant, and CEO of digital health company, Acupera. He completed his medical training at the Mayo Clinic and holds an MBA from Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management